It was inevitable. When you look at a tangle of fungal mycelium, sprawling threads and root-networks like wires, you can’t help but think, “Someone should plug a circuit board into this.” That day has come. Someone finally has.

Researchers at Ohio State University (OSU) have shown that common mushrooms can power electronic memory devices — proving that the future of computing might be just a little bit fungal.

Mushrooms as Computers? Yes, Really.

The new study, published in PLOS ONE and titled “Sustainable memristors from shiitake mycelium for high-frequency bioelectronics”, explores how the edible fungus Lentinula edodes (しいたけ) can act as a memristor, a circuit component that “remembers” its electrical state over time.

Memristors are key in neuromorphic computing (systems that mimic how the brain works) because they combine memory and processing in one device. Traditional memristors use rare‐earth materials, high-energy manufacturing, and rigid, inorganic substrates. The OSU team asks: what if you could grow them organically instead?

How the Experiment Worked

Here’s how the science played out:

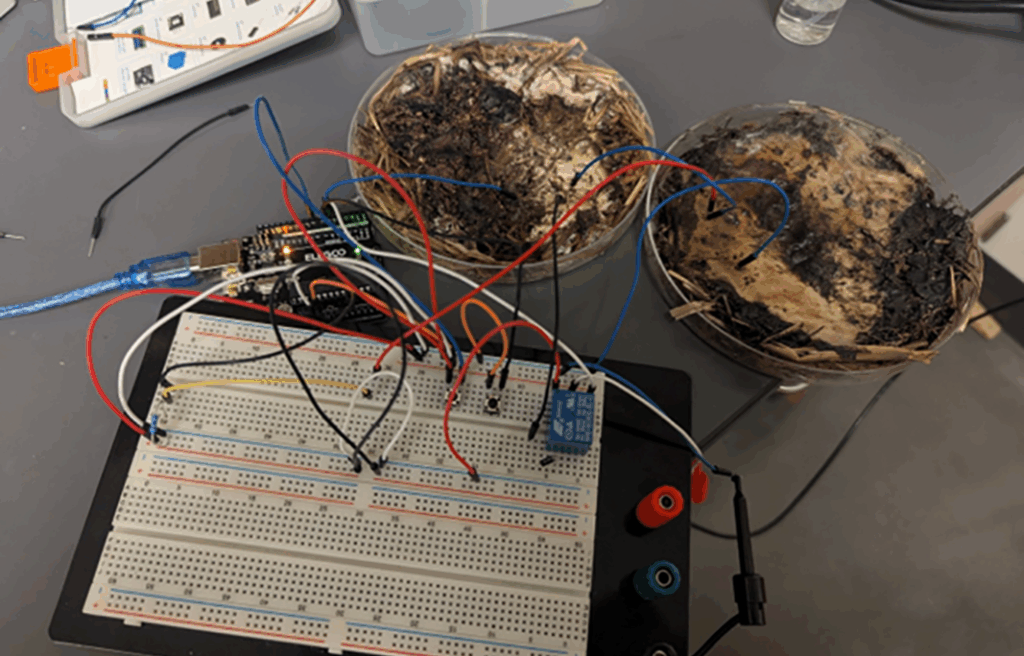

- The team cultured shiitake mycelium, letting the fungus grow into mats or networks of fine filaments.

- They then dehydrated the grown material so it became stable and could interface with electronics.

- Electrodes and wiring were attached to different zones of the fungal mat because different parts of the fungus exhibited distinct electrical behaviours. “We would connect electrical wires and probes at different points on the mushrooms because distinct parts of it have different electrical properties,” lead author John LaRocco explained.

- They applied varying voltages and frequencies and measured how the fungal memristor switched between electrical states.

- The standout result: the device achieved switching at up to 5,850 signals per second (≈ 5.85 kHz) with about 90 % accuracy.

In short: they built a functioning memory element out of mushrooms.

Why This Matters

The implications are incredibly exciting — if somewhat futuristic.

Some key advantages:

- 持続可能性: Fungi are organic, biodegradable, and can be grown at relatively low cost — contrasting with chips made from silicon, heavy metals or rare earths.

- Energy efficiency: According to LaRocco: “Being able to develop microchips that mimic actual neural activity means you don’t need a lot of power for standby or when the machine isn’t being used. That’s something that can be a huge potential computational and economic advantage.”

- Novel form-factors & resilience: The paper notes that shiitake mycelium has radiation resistance, which could make fungal electronics suitable for extreme environments (think aerospace, remote sensors).

- Neuromorphic & organic computing potential: Because fungal networks share structural similarities with neural networks (branched, dynamic, conductive filaments), they may lend themselves to brain-like architectures more naturally than rigid silicon chips.

But: The Current Caveats

Be sure to hold your horses however, it’s not ready to replace your Mac-book just yet.

Some limitations:

- The switching speed and accuracy, while impressive for an organic substrate, still lag behind the best inorganic memristors. Performance dropped as frequencies increased.

- Miniaturisation and scaling remain hurdles: growing fungal mats is one thing; integrating them into tiny, commercially viable modules is another.

- Long-term reliability, integration with existing chip-fabrication lines, durability under industrial conditions, all need further research. The authors themselves acknowledge this.

What the Researchers Envision for the Future

From the study and related coverage, here’s what the team sees ahead:

- Cultivation templates embedded with electrodes: They propose using 3D-printed molds to grow mushrooms directly into shapes and structures suited for electronics.

- Dehydration/preservation approaches: They show that the fungal memristors retained functionality after dehydration — meaning they can be stored, shipped and later powered up.

- Applications beyond standard computing: Because of their robustness and low-resource fabrication, fungal electronics might find homes in edge computing, disposable sensors, remote/outdoor electronics, or even space missions.

- Hybrid systems: Fungal memristors might integrate with other organic or silicon components to craft mixed computing platforms (maybe part silicon, part fungus) leveraging the best of both worlds.

Why the Mycelium Metaphor Fits

It’s more than just clever imagery. The mycelium network — the branching filament system that fungi use to forage, communicate, and adapt — already 顔貌 like a circuit board or a neural network. The electrical behaviour of mycelial strands (in many fungi species) has been studied and shown to transmit electrical impulses, adapt to environment, and “learn” in a very loose sense. This study simply harnesses that latent capability for computing.

The Bigger Picture: Computing’s Greener Frontier

In an era where energy consumption by data centres is skyrocketing, and electronic waste is a major environmental challenge, tech + biology synergies like this are especially appealing. The concept of biodegradable electronics, grown rather than manufactured in high-temperature factories, has been a dream for decades. This research brings it a step closer to reality.

Co-author Qudsia Tahmina puts it neatly:

“Society has become increasingly aware of the need to protect our environment and ensure that we preserve it for future generations. So that could be one of the driving factors behind new bio-friendly ideas like these.”

So… Should You Replace your SSD with a Shiitake?

Not today. Not tomorrow either. But you might imagine a future where your wearable health tracker or outdoor sensor uses a fungal memristor for a component of its memory, or where sprawling mycelial networks beneath a lab bench are wired up to handle part of a neuromorphic computing task.

In summary: This study doesn’t herald “mushroom laptops” tomorrow — but it を行います。 represent a bold leap into bio-electronic futures. The day when your computing substrate grows in a Petri dish instead of being carved from silicon is now a little closer.

And somewhere in the compost heap, the next generation of computing quietly sprouts.